|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

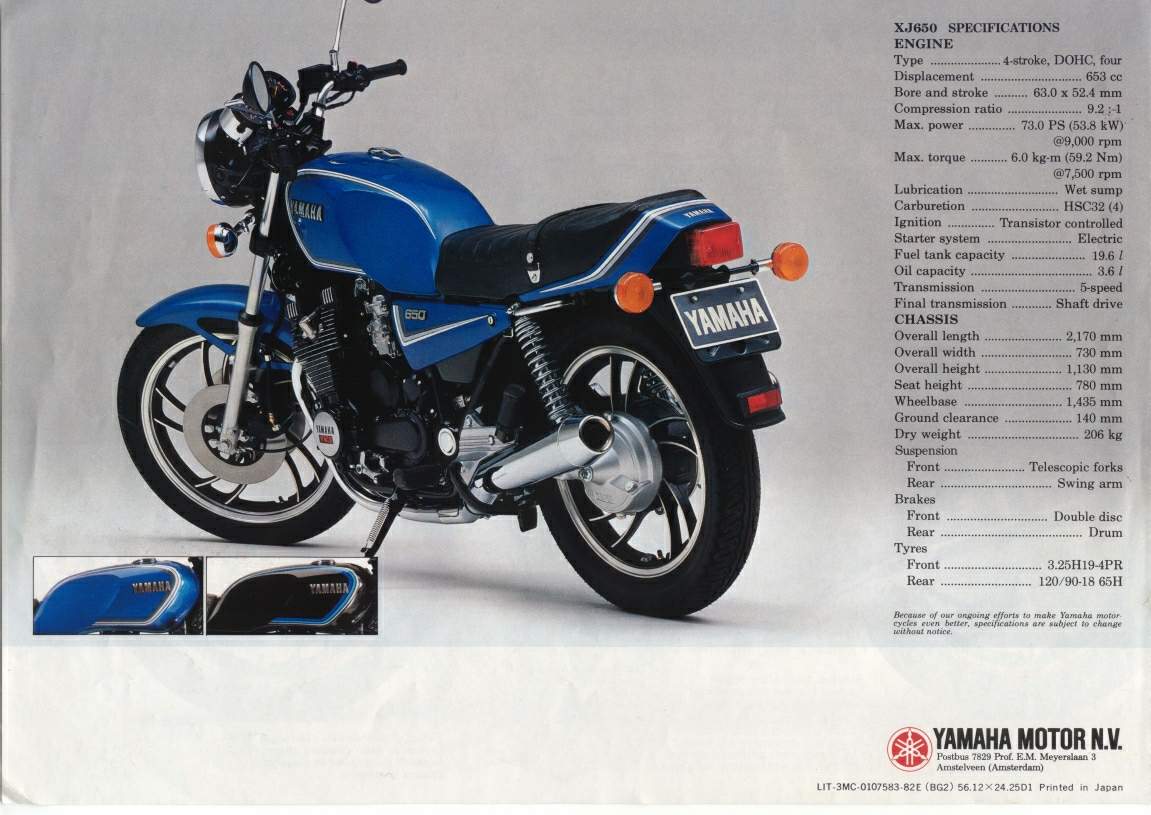

Yamaha XJ 650 Seca |

| . |

|

Make Model |

Yamaha XJ 650 Seca |

|

Year |

1981 |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, transverse four cylinder, DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder, |

|

Capacity |

653 cc / 39.8 cu-in |

| Bore x Stroke | 63 х 52.4 mm |

| Cooling System | Air-cooled |

| Compression Ratio | 9.2:1 |

|

Induction |

4x 32mm Hitachi carburetors |

|

Ignition |

Transistorized |

| Starting | Electric |

|

Max Power |

71 hp / 51.8 kW @ 9400 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

57 Nm / 42 lb-ft @ 7500 rpm |

| Clutch | Wet Multiplate; 7 Steel 8 Friction |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

| Final Drive | Shaft |

| Gear Ratio | 1st 2.187 (35/16) 2nd 1.500 (30/20) 3rd 1.153 (30/26) 4th 0.933 (28/30) 5th 0.812 (26/32) |

| Frame | Tubular steel dual cradle frame |

|

Front Suspension |

36mm Kayaba forks |

| Front Wheel Travel | 142 mm / 5.5 in |

|

Rear Suspension |

Duel Kayaba shocks |

| Rear Wheel Travel | 93 mm / 3.6 in |

|

Front Brakes |

2x 268mm disc 1 piston calipers |

|

Rear Brakes |

Drum |

|

Front Tyre |

3.25-19 |

|

Rear Tyre |

120/90-18 |

| Wheelbase | 1445 mm / 56.8 in |

| Seat Height | 780 mm / 30.7 in |

| Ground Clearance | 145 mm / 5.7 in |

|

Dry Weight |

206 kg / 465 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

19.5 Litres / 5.1 US gal |

|

Consumption Average |

48.6 mpg |

|

Standing ¼ Mile |

12.6 sec. / 171 km/h |

Okay, might as well get the grovelling over first. Those of you who had the undeniable good taste to buy last month's ish may have noted a pious hope that we'd be testing Honda's CX650 this time round. Ahem. Well we near/ytested it. Enraged and infuriated beyond reason during yet another fruitless trip to Big H's UK HQ in search of an increasingly elusive VF750F (see last ish for that particular tale of disappearing Hondas), I commandeered a CX with the intention of holding it hostage.

Alas, a park keeper with hismindon things herbaceous forced another staffer into a conflict situation with some wheelbarrows by attempting a U-turn in front of the CX in his van. Luckily only minor damage was incurred by barrows or Honda but, while the barrows were doubtless quickly patched up, the Honda was sidelined by a small scratch on its flyscreen. And where was the vitaK?) replacement part? In Ghent . . .which, before you reach for your atlas, is definitely not in this country. No CX650.

Frantic 'phone calls were made to the Other Importers, the result being someone else's shaft driven 650cc four-stroke — to whit an XJ650. And this time, of course, with YICS. YICS, as well as being the Mongolian word for 'no', is short for Yamaha Induction Control System. Unless you've actually been in Mongolia these last three years, saying 'yics' whenever offered a pint of goat's milk beer, you'll doubtless know that YICS is essentially a no-moving-parts add-on to the intake side of Yamaha four-stroke motors aimed at improving combustion efficiency and fuel economy.

It consists of a pipe running across the rear of the cylinder head from which four small passages run up to the main inlet tracts, which they join just behind the valves. As each piston starts its induction stroke it sucks mixture from both the main and YICS inlets. As the YICS inlet is a much smaller diameter than the main one, the mixture travels up it at a faster rate and, on meeting the main charge, gives it a swirl as it spills into the combustion chamber. Yamaha reckon the system's a good 'un when it comes to getting good power and gas-mileage without the complication of using four valves per cylinder. And to be honest, good power and gas mileage were not the original X|650's strong points . . .

The X), you'll maybe recall, was billed as Yamaha's answer to those hacks and punters who persistently decried the japs for bowing only to the tastes of American riders bent on cruisin' evil, wobbly, chain-consuming, gas-guzzling megalumps down Interstates at 55mph. Feedback was in the in-word in 1979/80; Yamaha NV in Holland went in for some heavy polling of Eurobikers as regards their taste in machinery. The results were fed back to Japan where the designers were contemplating Yamaha's first new four-stroke multi since the XS750/850 and Excess Eleven.

The upshot, it transpired when first details were released, was a nice-looking, no nonsense 650. Low, slim, shaft-driven, unencumbered by complicated suspension or digital widgits, it sounded both sensible and fast — especially with a claimed 73bhp on tap. Reactions to the XJ650 when it arrived were, however, mixed. Good marks were handed out for comfort and performance, medium points for transmission smoothness and handling, and rotten ones for power characteristics and fuel economy.

Yamaha's answer was to add YICS last year, along with dropping the rather tasty silver paintwork of non-induction controlled models for a rather heavy handed metallic blue. The only other changes I could see on the test X| I collected from Chessington were new indicator lenses and something more up to date in the way of Bridgestone rubber on the cast italic wheels.

Seen as a good-looking bike a couple of years go, the XJ's styling has been left behind by the tide somewhat. Or maybe — sudden thought— it's actually jap late-'70s-classic. That outsize 8in H4 headlamp and separate chromed instrument housings above an unfashionably large 19in front wheel hardly cut it with the GSX/GPz/CBX mob with their integrated fairings, tanks, seats and tails. On the other hand I'll bet the Yamaha's cheaper and easier to repair after a spill.

When cold the motor fires up easily with a little help from the choke, whose lever is conveniently positioned under the left handlebar switchgear cluster. Despite the sparse finning on the head and barrels and close-set pots, the motor takes quite a while to warm-up fully: it'll pull away after a few seconds so long as some choke is left on but on a cool morning it takes a few miles before the XJ'II run smoothly and cleanly. On the other hand the motor gets very hot on really warm days (do we ever get those any more?) so maybe the five-row oil cooler isn't just a gimmick.

A peculiarity of the XJ series is the use of oil level warning lights instead of the more usual oil pressure — maybe Yamaha have loads of oil level switches left over from the 2T lube tanks of RD strokers they don't build any more . . . The red oil idiot light flickers briefly when the starter button's pressed to show it's working but there's a sight window below the clutch cover for a visual check — except in cold weather when it mists up with condensation on the inside.

Once running the one truly unique feature of the XJ650 manifests itself. Instead of emitting the usual four-stroke, four pot threshing and grinding noises, the mill puts out a penetrating high-pitched whistle guaranteed to turn pedestrians' heads at up to 200 yards (183 metres). If you've only bought an XJ as a humble, low maintenance workaday hack it gets pretty embarrassing when folks start staring at you as if you're on some freaky turbo. On the other hand the XJ does sound a bit like a jet fighter barrelling up a runway if that's the way your fantasies lie. It's hardly relaxing, though, — even at a steady 60mph and 4250rpm the XJ's lump sounds like it's turning a coupla zillion revs, which is okay on a cruise down the Kingston bypass but begins to grate on a 200-mile trip. Only thing to do is keep the thing at 90mph or more where wind noise and other mechanical rumblings drown out the whistle. Like so many things about the XJ650, you either learn to put up with it or find another scoot. The weirdest thing about the engine note is the effect on it of a slight misfire (which usually manifests itself if moisture gets into the plugs' metal suppressor caps), whereupon the whistle becomes a bubbling noise very akin to the sound of someone farting in a bath.

One aspect of the XJ which definitely doesn't have to be just tolerated is the seat and riding position. The seat is flat and firm; very comfortable over long distances and easily large enough for two fatty posterior regions. Footrests are slightly rearset — not quite far enough back for sustained high speed bashes but comfortable enough for normal use up to around 80 per. Together with shortish, down-curving LC-type bars, the seat and pegs make for all-day comfort.

If you take the XJ's sweet shaft drive and ample provision for hard and soft luggage stowage into account as well, the foregoing sounds as if it's a reasonable touring proposition. Unfortunately the character of the original XJ's motor was almost completely at odds with most people's idea of the compleat tourer's powerplant.

Like most high horsepower middleweight fours, the XJ engine needed plenty of revs to find significant power. Most of what you'd call exciting performance comes in around seven grand and runs up to the 9000rpm mark. After that it's up to wind, gradient and crouch to determine whether it'll stop pulling or run on past 9'/2 thou and into the red zone. Lower down the original version's rev range, there was an area of useful poke between 2500 and 5000rpm: below that it gasped at a handful of throttle and above it the motor felt pretty flat until seven grand.

Translated into road terms, it meant the old bike possessed adequate but not startling performance in top (fifth) gear up to about 70mph and then took its time to reach 90. In first gear, especially when hot, mucho revving and clutch slip was necessary to avoid fluffed getaways from lights. Fast travel was a mixture of twist-grip wrenching, incessant gear changing and, if the revs dropped into the midrange snooze zone, waiting. Hard charging with max use of throttle and gear pedal disguised the lumpy powerband but the trade-off was fuel consumption down in the 30s and, of course, colossal amounts of whistling and fussy noises down below.

It'd be nice to report that adding YICS has transformed all that. But I can't. It has made a few subtle improvements: the motor's less asthmatic at very low revs and the midrange power trough isn't so noticeable but the power gradient is still uneven. Fuel consumption is improved, however. A 100-mile thrash to MIRA on A roads, holding 90-100mph most of the time, followed by a couple of dozen miles of redlining abuse at the track pushed consumption down to lever you push in to cancel manually.

The seat hinges up rather than lifts off; a short rod holds it up. A typical lap toolkit sits in a tray over the airbox and contains enough spanners and alien keys for simple servicing and wheel removal. The plastic coated security chain squeezed into a compartment above the swing arm pivot won't deter anyone with a decent set of bolt cutters but it's useful for chaining helmets to a wheel while you go shopping or whatever.

The 4.3gal tank gives a full range of around 200 miles, usually going on to reserve at about 160 miles. The offset, lockable, fuel cap is a neat idea if you want to get a lot of fuel in without heaving the X) onto its centrestand but it isn't in the best place to line up with cut outs in tank bag bases.

That big 8in searchlight on the front is adequate for 70-80mph riding at night but it could do with a sharper cut-off and less spread. Luckily there's plenty of reserve power in the X)'s 270W alternator if you want to mount a couple of spots to give more penetration. Paintwork on the tank and frame looks good but it's pretty thin and tends to start flaking off engine mounts and the front of the metal front mudguard after a few thousand miles.

The mirrors give a useful rear view but tend to seize up on their ball sockets at the top of the stems. There's little problem stopping the X), thanks to twin lOin stainless discs up front and an 8in sis drum down back. There's not a lot of feel at the handlebar lever, though, and emergency stops call for a hefty squeeze. Again, it'd help if the lever was nearer the twistgrip instead of being a finger-tip stretch. The discs work very well in the wet, too. No problems with the Bridgestone boots on wet surfaces either.

We achieved a two-way average top speed of 115mph at MIRA, lying flat on the tank, with a best of 117.3mph. Sitting up speeds were 109.2mph best and 106.5mph mean so the X)'s capable of being a genuine ton up cruiser if necessary (or if your neck and wrists can take it . . .). The YlCS-engined bike's time of 13.47 sees up the quarter-mile is exactly the same as the non-YICS version we tested in December 1980 so the new technology makes the 650 no quicker though a little more flexible and less thirsty.

The X)'s main rivals at the moment are Suzuki's two 650-four shafties, the Katana and GT. Lumped together the Suzukis provide much the same package as the XJ: shaft drive, plain, strong, two valves per cylinder motors an unfussy chassis and equipment. But Suzuki went one step further than Yamaha and produced both a sporty version and a general purpose/touring mount. The Katana may seem a bit of an eyeful at first but it's as fast as the Yam, little thirstier and handles much better. The CT is only a tad less impressive on speed and handling and is definitely the pick of the two for two-up work, though it looks bulky and sports an unfashionable amount of chrome.

Unfortunately the Yamaha loses out to both on price as well. The Suzukis are between £100 and £140 cheaper on list price and the differential carries through to discounts where X]s can be picked up for around £1750 and the Katanas for £1650. The only slot the X)650 seems to fit into is a halfway house between the two Suzukis where it scores over the GT on looks and the Katana on two-up practicality. Which brings us back to the compromises which threaten to screw up what should've been a good fast tourer.

Yamaha's sales and stocks situation is much better in Europe than it is in the States and latest home sales charts for all manufacturers seem to show there's plenty of life left in the over-500cc four cylinder market but there are apparently no plans for another revise of the 650. If they're going to compete against the best of the rest, maybe it's time there were some.

Source Bike 1983

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |