|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

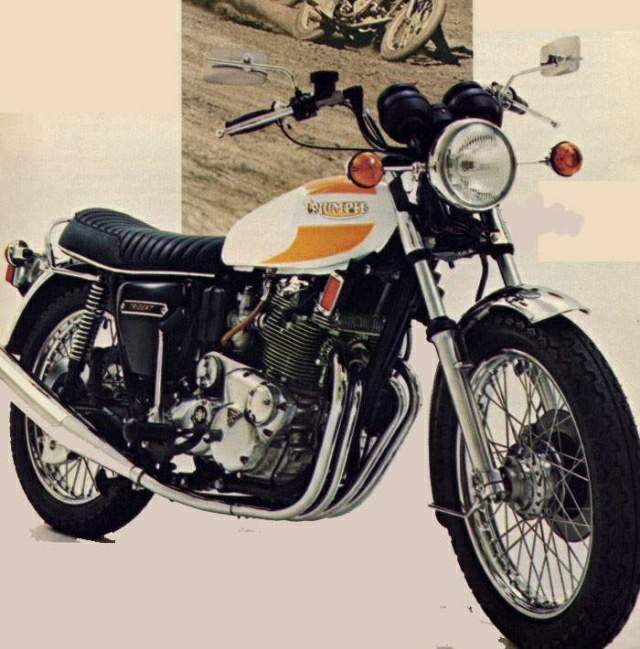

Triumph Trident T160 750

|

| . |

|

Make Model |

Triumph Trident T160 750 |

|

Year |

1975 |

|

Engine |

Transverse three cylinder, pushrod OHV, 2 valves per cylinder. |

|

Capacity |

741 cc / 45.2 cu in |

| Bore x Stroke | 67 x 70.5 mm |

| Compression Ratio | 9.5:1 |

| Cooling System | Air cooled |

|

Exhaust |

3-into-4-into-2 |

|

Induction |

3 x 27mm Amal Concentric 626 |

|

Ignition |

Individual points, coils |

|

Starting |

Electric |

|

Max Power |

43.8 kW / 60 hp @ 7250 rpm |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

|

Final Drive |

Chain |

|

Frame |

Tubular steel cradle |

|

Front Suspension |

35 mm Telescopic forks |

|

Rear Suspension |

Twin Girling shocks, adjustable preload |

|

Front Brakes |

Single 254 mm disc |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 254 mm disc |

|

Front Tyre |

4.10-19 |

|

Rear Tyre |

4.10-19 |

|

Wheelbase |

1473 mm / 58 in |

|

Ground Clearance |

165 mm / 6.5 in |

|

Dry Weight |

228 kg / 502 lbs |

|

Wet Weight |

250 kg / 552 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

19 Litres / 5.0 US gal / 4.2 Imp gal |

|

Braking 48 km/h / 30 mph - 0 |

8.2 m / 27 ft |

|

Standing 1/4 Mile |

13.95 sec |

|

Top Speed |

193 km/h / 120 mph |

| . |

The swan song of the British motorcycle industry

came in 1968, when the BSA-Triumph group launched a new three-cylinder

model, built as the Triumph Trident and BSA Rocket. Excellent in conception,

with an outstanding power unit, they proved to be overpriced, due to a

combination of an overcomplicated specification and the cost of developing

two different versions of the same design. The coup de grace came

when Honda launched its more economical and robust 750cc four.

One Last Effort

However, in 1975, the British industry made one final effort, combining

Norton-Villiers and Triumph-BSA in a single distribution network, with a

standardized model range hastily brought in line with current taste.

At Last an Electric Start

To comply with American standards, the British relocated the gearshift from

its traditional place on the right to the left-hand side of the machine and

at last fitted an electric starter. Production of the BSA Rocket was halted

and this ultimate T160 incarnation of the Trident had the inclined cylinders

of the BSA, a rear disk brake and more flowing lines. This hasty facelift

was not enough, and the Trident ended up heavier and slower. In less than a

year, output had fallen to a trickle because the Trident was not competitive

pricewise with its Japanese rivals.

Norton Commando vs Triumph T160V

Norton Commando

ANDOVER on a cold, damp Thursday morning: about as uninspiring as any place can be. The weatherman promised snow but we already had more than enough rain, thank you very much. By eleven-thirty the only bright spot so far had been when ace cameraman and travelling companion Bob Carlos Clarke wandered off down the lurching corridor train in search of the smallest room. Within a minute of his disappearance the train pulled into Andover station and Bike's road-test duo were gripped with the cold fear realisation that they were en route to the grand, all British, all electric, front cover photo session without a photographer. A little old lady came to our assistance as we rushed an assortment of equipment and riding gear onto the platform. A porter slammed the carriage door, the train ground away in one direction — and Bob shambled up in the other, grinning. Bet he flushed while he was in the station.

Commando, to a lot of people, is a dirty word. There isn't anything that hasn't gone at some time or other; head gaskets, cranks, exhaust systems — you name it, sooner or later it's blown, broken or fallen off. I'd only ever ridden a Norton twin on a couple of occasions, never owned one; everything I'd heard was second or third hand, not exactly a sound basis for constructive criticism (but food for thought perhaps?). On the other hand, what I'd seen looked good; Commandos blasting this way and that, a healthy exhaust note and an unmistakably British look.

To dismiss the Mk 3 as just another Commando (yawn) was obviously out of the question. There were too many changes to last year's specifications, too many great big galloping strides forward to cross it off as yet another variation on Bert Hopwood's original theme. It was time for the good old open minded approach. Andover station, the state of the nation, the weather and all else aside.

The only snag was, of course, that despite all the intriguing new bits and pieces and my enthusiasm for the truth above all else, the Mk 3 Commando looked unmistakably like last year's Mk 2a, the Mk 2 before that and etc, etc.

Lesson no. 1: don't be fooled by appearances. There are somewhere in the region of 150 new or changed parts on the 1975 model which all in all add up to one hell of a bike. For the first time in several years the Commando is able to compete on an even basis with all the other bigsters at the upper end of the market, it's no longer a second rate alternative to a real supabike. If you'd been down in Andover during the rainy season you would have seen what I mean.

I'll kick off with the obvious, though since last month's Ducati test I'm already on tricky ground. (Look it up later will ya, I'm up for three speeding offences in hall an hour's time and they don't like you to be: late.) The Norton has an electric starter; it says so on the side panels and if you nose around behind the barrels you'll see the gizmo itself, the addition being more apparent from the left hand side where the gear drive drops into the primary chain case.

The unit is solenoid operated and manu factured by Prestolite (press-to light, get it?) in the USA. Finger-tip control comes from the new US standard layout green forgo button on the right bar, the starter is power ed by a heavy duty Yuasa battery, and that in turn is kept fighting fit by a 120 watt Lucas alternator.

It couldn't have been more than a couple of days before I climbed aboard the beast itself that we received a rather unsettling letter from an American reader. To wit, he had heard (same old problem) down at the local bike shop that the Norton's electric starter wouldn't turn the motor until the mill had been fully run in. Maybe somebody was out to make a few easy dollars — first buy a Norton, spread the rumour amongst the Jap bike and Harley owners, take on a few bets and then clean up. Sure's there's a little piece tucked away in the handbook that recommends freeing the engine with the foot lever before cold starts, but I didn't get round to reading it until the test bike was long gone and I hadn't noticed any problems. On the grottiest of mornings, with the mercury in the minus zone, there was always a slight hesitancy as the first piston came up onto compression, but with flooded carbs and full choke a second prod at the button set things in motion.

Another obvious newie is the left hand gear change, right hand rear brake and the standardised (that'll send shivers down a few spines) shift pattern. Although shifting is now up for up, down for down, the basic box internals haven't altered and the feel at the lever, a long, definite action, remains very very British. Those weened on nimble toed Nippon changes may find themselves missing a few cogs; personally (here comes a blatant all-out bid for life membership of the NOC) I thought the action complemented the overall style of the machine and with gobs of torque available at the twist of the wrist there was a total absence of the multi-cylindered fussy urgency that has made modern biking such a frenzied affair.

The relocation of the gear lever has been effected by an internal crossover shaft running to the front of the main gear-box assembly, emerging through the primary chain case just forward of the clutch. This has meant that at long last the gear-box is a fixed unit, although still of separate construction, with engine and gearbox centres remaining constant. Chain tension is maintained hydraulically, and in an effort to "improve oil sealing" — what a pity the brochure doesn't carry the conviction of actually achieving oil sealing the case outer cover is held in place by peripheral screws. At least somebody's been taking notice of all the waterproof boot argy-bargy, and if you really must know the truth, it works, dammit, it really works. In fact, while we're on that age old topic of conversation, it gives me great pleasure to announce, gentlemen, that the merest hint of lubrication on the outside could only be found at the junction of the rev counter cable and the crankcase, and only then after continuous high speed cruising.

Which brings us rather neatly to the Norton in its element, bopping down the blacktop in reassuringly confident style. The power characteristics of the motor reminded me of the Harley Sportster we tested in December '74 — the torque is absolutely unbelievable, catapulting the machine off the line, making constant gear-changing in Search of a power-band unnecessary. A total of 58 horses are developed just below six grand, after which the slugging momentum drops off noticeably although not before the speedo has registered a very healthy ton-plus figure. After riding the Commando on the street I'll have to admit that the speed trap findings came as something of an initial disappointment. On long stretches of open motorway the extremely wide American specification handlebars left the rider stretched like a sheet in a gale force wind, so in a bid to reduce fatigue and a permanent death lock on the hand grips I was obliged to keep things down to a sane, and would you believe it, legal level. However, scratching back from Norton Triumph International's Kitts Green establishment with Bill Haylock on the new Trident, I could find absolutely nothing lacking in either performance or handling and at no time was the Norton obviously outclassed by the amazingly swift Triumph three.

Undoubtedly the Isolastic engine mounting set-up raised more than a few eyebrows when it was first introduced, but that's hardly surprising when you consider the long-standing reputation of the Featherbed frame it had to follow. Nowadays it's something we take for granted but even so changes have been made in order to iron out the last of the bugs. The Isolastic rubbers are now bonded together to prevent shifting, and the original shimming method of adjustment — a ridiculous imposition, no doubt born of afterthought, to place on any owner has been superceded by a lockable thread.

As is to be expected, while the Isolastics absorb all the engine's high frequency vibration, slow idle judder is quite pronounced despite the addition of a spring loaded support to the head steady. At first the sensation of the motor quivering around at tick-over is er, rather strange, but a little high speed ear 'oling soon sets your mind at rest about everything being according to plan. Besides, try blipping the throttle on a BMW at standstill — if you're the nervous type that really is food for thought.

The 850cc power unit, regularly the root cause of much gnashing of teeth, has been given new, thicker walled crankcases and main bearing widths have been extended. The Commando crank assembly, a forged steel bolt-up affair running in roller bearings, has long been regarded as the height of notoriety, although in fact the reputation was earned by the earlier 750s. Relying on two bearings for support, it inevitably whipped at high revs and overstressed the edges of the bearing rollers. The adoption of FAG Superblend bearings, the rollers of which have a slight taper thus eliminating line contact, overcame the problem and now even the crank itself has been beefed up. Con rods are shot peened to eliminate surface nicks.

Looking back through past road tests it's quite remarkable how performance figures have been falling off year by year. Was a time when the 750 Norton nudged the 120 miles per line, but in common with most contemporary machines the latest, larger twin is well down in the speed stakes. Obviously it's carrying a lot of extra weight, some 50 lbs in fact, and stringent overseas anti-noise and pollution requirements have a lot to answer for. The engine breathing system recycles oil mist first through the oil tank and then via a separator into the induction system, the small amount of remaining oil being passed directly into the inlet manifold forward of the carburettors. The moulded plastic air filter box is designed for maximum inlet noise suppression, the filter itself being an oil wetted foam element.

The exhaust silencers are billed as being "superquiet", which couldn't be nearer the truth. Identical units are fitted to the Trident, but while they give the three a rather satisfying raspiness — to onlookers at least — they reduce the Commando's note to a very mediocre mumble, totally inaudible to the rider encapsulated in a full face helmet. At the other end of the system, the pipe flanges have been replaced by spherical swaged ends to allow unstressed pipe alignment and bring an end to the constantly recurring loose pipe bugbear.

When you consider how apathetically the Norton twin has been projected in the past (aren't the changes we've already discussed enough indication of a long neglected potential?) it's so refreshing to see evidence that every last aspect of the machine has been given consideration in the light of current market trends, technical advances, and plain old owner requirements. For once we haven't been served up with last year's model (faults an' all) in a simply different colour, with a different seat or a different silencer.

One such example is the introduction of a rear disc brake, a Norton Lockheed item identical to that already mounted up front. The foot pedal is pivoted on the footrest support arm and is connected directly to the combined master cylinder and hydraulic fluid reservoir. The hoses to both brakes are armour protected and the connections have been routed neatly and well out of harm's way. The old drum rear stopper was never anything to write home about; like so many things, it worked and that was deemed sufficient, but thanks to a characteristically heavy lever pressure the rear disc is capable of rapid yet safe retardation. A very pleasant side to the braking is that at low to medium speeds you don't get hauled unceremoniously to a tyre squealing halt with your passenger flattened against your back and your bum thrust a good six inches onto the top of the tank, while braking in the heat of a high speed moment is as effective as hitting the brick wall you will be fortunate enough to miss.

The front brake caliper is now mounted on the leading edge of the fork slider and the whole unit has been switched over to the left hand side. A reason has been given for both changes, yet while the cynical will maintain that the forks have simply been turned through 180 degrees for the hell of it, it would require the knowledge of a braking, handling and turbulence characteristics expert to get to the bottom of the matter, particularly since one of the reasons is a direct contradiction of current practice on the Trident stablemate.

The left hand mounting is supposed to improve steering balace in conjunction with the right side mounting of the rear disc. Fair enough. The forward mounting is supposed to prevent the accumulation of road grit inside the caliper with resultant excessive wear on the pads. Certainly this was a fault with the previous set-up, pad wear being increased by as much as 80 per cent in bad weather conditions with the additional horror show aspect of it being possible to eject pads under braking if wear hadn't been regularly monitored and new pads fitted in time. The wiper blades that are rumoured to be in the offing would end the controversy once and for all, but they were not evident on our test bike. Over to you, Mr Expert.

Further requirements dictated by American law can be found at either end of the handlebars. The control switch units are of a new design finished in flat back with the various switch functions engraved and picked out in white to comply with US legislation. On the right above the starter button is a red ignition cut-out, and the headlight / parking light switch. The brake lever is of polished forged aluminium forming an integral part of the handlebar unit which also includes the master cylinder and reservoir. Rear view mirrors screw directly into either unit and although they weren't fitted to the test bike they are listed as standard equipment.

Bottom left is a combined horn / headlight flasher button which is mercifully easy to locate in a hurry, turn indicator switch and hi/lo (uuugh! what price patriotism now, my friends?) selector. Even though all the switches and buttons are located at the back of the units, they don't look particularly waterproof; in view of the thoughtful rubber ignition lock shroud and steering lock bung I'd have expected something a little more secure against the elements despite the fact that throughout the rain sodden test period no problems were experienced. The twistgrip, by the by, has a quick action operation and both throttle and clutch cables are nylon lined for sooper smoothness.

Four warning lights are sited on a panel between the speedo and rev counter, latest addition to the original line-up being the neutral indicator coloured green. Main beam warning light is now regulation blue. There really doesn't seem to be much point arguing the toss over the American stipulations (Canadian models have the headlight wired in with the ignition); they exist and if you want to sell bikes over there you have to comply. I suppose it is just possible that a number of affluent Yanks will be saved a few premature grey hairs as they chop and change amongst their vast stables of latest model two wheelers, but over here it only adds to the cost. And after all, a century or so's motorcycle production is going to take quite a while to wind up on the mantlepiece or the junk pile.

So there you have it. open minded approach et al. I for one would gladly brave the horrors of Andover station for another ride on the Commando Mk 3, for a chance to really absorb the character of the machine, to appreciate it and to enjoy the very definite style of biking it offers. For that's a very important thing with the Norton — its character. It's something that tends to get sidelined with the majority of modern machines, but once you've ridden a bike like this you suddenly realise that you've been missing out.

The Commando complements the Trident surprisingly well. The three is sleek and fast, really fast, and in its latest guise a front line contender in the big bike world. The Commando provides the raw, brute force back-up of relentless low revving power, the kind of action suited to effortless day long cruising with the box set in top and a lazy right hand offering a little more or less throttle as the situation demands. At a glance it may not have changed very much, but in fact it has changed a great deal. It is very much a new machine, at long last fulfilling the potential that until now has remained so ridiculously unex-ploited. Above all else, the Mk 3 is definitely not just another Commando.

Phil Mather

Triumph T160V

SALISBURY Plain, stretched out bare and open to a heavy grey sky, is bisected by a thin ribbon of tarmac, one end of which unwinds in a blur under the front wheel while the other disappears over the edge of the drab, wintry countryside. Stonehenge's primeval silhouette looms out of the empti ness of the plain and then vanishes behind my right shoulder.

This visual tableau of stark, primitive forms is accompanied by a rumbling, growling noise that could almost be coming from the massive lungs of a Tyrannosauru Instead, it's bellowing from the three lusty cylinders of the new electric start Triumph Trident I've just collected from the nearby Andover factory.

Oddly, the elemental landscape seems quite in accord with the feeling of riding this, the latest, most complex machine to be launched on the market by the British motorcycle industry. Thankfully sophistication hasn't spoiled what has always been a good bike. It's polished blemishes away but left that raw edge that is the quintessence of British biking.

Roller-coastering over the gentle swells and dips of the road I just relax and take in the feeling of space and the exhilaration of riding one of those big, honest bikes that demands very little of you, but gives all you could want.

Still a distinctively British bike, the Trident represents a biking ethos that has been declining these past few years as the sadly shrunken state of the British industry testifies. With so many super-smooth studs dashing around on flash multis and screaming little two strokes, admitting to a partiality for the simple joys of British biking is likely to get you ostracised from trendy society. What the hell, I'm not going to start apologising for going into raptures about the Trident's charms. It's not a question of blind patriotism, it's just that I love that noise, the power and that hefty feel.

When the Triumph Trident was first sprung on the unsophisticated motorcycle market of the late sixties circumstances conspired to deny it the popularity it really deserved. A lot of bikers were ready for excitingly exotic machinery to break the monotony of the ubiquitous parallel twin, and the Trident should have taken the world by storm as the first of the seventies generation of so-called superbikes.

But just a few months later the inscrutable Orientals outbid Triumph in technological one-upmanship when they launched on a spell-bound public the 750 Honda with no less than four cylinders. Exotica from the mysterious East seemed far more appealing than any bike from the grimy Midlands, and a four was a breath-taking step into the realms of super-technology, or at least it was back in those naive days before we became blase with a surfeit of threes, fours and sixes. Sadly, that left the Trident, and its BSA stablemate, the Rocket-3, in a state of limbo in a rapidly changing biking scene that must have left the British designers feeling deflated and befuddled.

So the Japanese onslaught took the wind right out of BSA-Triumph's sails (and sales), the Rocket-3 faded into history and the Trident underwent a few superficial and half-hearted styling changes which demonstrated that Triumph just weren't sure where they were going.

For a brief interlude it seemed they'd actually summoned up the resolve to launch something bravely new and different, in the shape of the Craig Vetter styled Triumph X-75 Hurricane (tested in the March/April '73 issue of Bike). But then it seemed as though the more conservative elements of the staid Meriden management got windy about it, and very few were produced before it went to an early grave like so many other good ideas.

The Trident just didn't have the style to cut it along with the rash or more exciting multis that sprang up from over the seas. Sure, it was a great bike to ride, but many potential buyers were seduced away by the glitter of chrome and electric starters. Anyway, with all the production problems the muddled British industry was facing, what was the point of them stimulating a demand they did not have the resources to satisfy?

But something had to change if the Trident wasn't going to fade away into obscurity. Thank God it's happened at last, and I just hope it's not too late to make up for the acres of ground lost in the first seven years of the Trident's life. If the Trident had been like this seven years ago there wouldn't be half as many Honda fours on the road now. At last it can stand up for itself among the ranks of the world's best and most exciting heavy road-burners, without looking inadequate or inferior.

For me, riding the Trident was something of a re-discovery of the joys of British biking, and a glad realisation that the sickly remnants of the country's industry is capable of presenting its products with the sort of style and finesse today's discerning market demands.

With three models representing the sum total of the NVT's range, including the Bonneville twin workers' co-op special, test bikes don't come our way very often, and we get to accept the values of Japanese designers as the norm, purely because we ride so many of their bikes. But the sight, sound and feel of the new Trident brought back the good feelings I had when I first rode one of the threes, the BSA version, back in 1970. An overall impression of solid, honest machinery hits you as soon as you punch the new starter button and the motor rumbles into life with a deep throated, purposeful thundering, almost like a big V8 diesel.

The Trident's sound, although somewhat emasculated by the new Norton type silencers to satisfy those insidious American vehicle regulations, is still as evocative as it always was. Anyone who has heard the soulful wail of a Trident on the race tracks; will know what I mean.

We picked up the Trident from Kitts Green, home of the NVT development shop, and having ridden the Norton there from Peterborough, the differences between the twin and the triple felt all the more marked. Although) both bikes' heritage stamps them with that distinctly British character, they each have a very individual feel.

Despite the frills and finery, the Commando's attraction is still that of the unsophisticated punchiness the parallel twin is known and loved (and hated by some) for. But the triple's appeal is more subtle. It lacks the Norton's hefty off-the-line torque, but makes up for it in a consistent surge of smooth, solid power that goes on churning out long after the twin runs out of steam.

The Trident is, in fact, one of the fastest bikes we've ever put through our electronic speed trap. It recorded a staggering oneway best of 126 mph. I could hardly believe it when I went back to look at the speed on the clock after my first run through the trap. Admittedly there was a moderate tail wind, but minutes before in identical conditions, the Commando had only managed 111 mph. It surprised everyone at the factory too: we'd been told that the extra silencing, air filters, etc. had cut the power.

Perhaps it was an unusually good motor, but it went like a rocket and just kept on revving. At that recorded speed of 126, the motor was in fact a couple of hundred over the recommended safe max revs of 8,000. Either the company's claimed power output figure of 58 bhp at 7,250 rpm is rather conservative, or all the opposition are lying about their power output figures.

Standing quarter times would have been significantly faster I'm sure, but for a slipping clutch. Under normal road conditions the clutch gave no problems, but as soon as it was subjected to the brutal punishment of being dropped in while the motor screamed at 8,000 rpm it slipped. Being a car-type single dry plate unit, it survived this sort of treatment better than the normal multi-plate type would. Half a dozen runs failed to have any permanent effect on the clutch, as soon as it cooled down it was perfectly OK again under normal conditions. But the slip meant that instead of catapulting off the line, the Trident just eased away until the clutch began to bite, which wasn't until second gear was notched up. Then the bike just powered up the airfield strip like a Phantom jet fighter on red alert. Without the clutch problems, times in the low thir-teens would have been no sweat. As it is, 13.77 sees still ain't bad by any standards.

The Trident's riding position feels immediately more functional than that provided by the Norton's high and wide US export bars. The Trident's flat, narrow bars and low seat give the sort of easy touring stance that British bikes used to have before they started pandering to the whims of easy-riding Yanks. It's comfortable and practical for long distance touring, or wriggling through metropolitan traffic.

Handling has a lot to do with the characteristic British feel. It's not as taut and responsive as some Italian machinery, but it gives a feeling of security and supreme confidence I've never experienced on any Japanese heavyweight. It sticks firmly to a predictable line, refusing to be deflected by bumps or rough road surfaces, and makes it easy to relax and enjoy the ride even when you're scratching around twisting country roads.

After the Norton motor's lazy pulsing, the Trident seemed hopelessly undergeared as I headed homewards from Kitts Green, until a glance at the tacho told me the three-pot mill wasn't spinning half as fast as I thought. In actual fact, I quickly discovered the Trident could lug just as well at low revs as the Commando. Perhaps not with quite such a crisp response, but smoother than the twin, which feels lumpy when you let the revs drop too low. It's surprising how the Triumph is content to bumble sedately along town streets in top gear, but to get things moving you've got to rapidly drop a couple of cogs.

So cruising homewards, the tarmac effortlessly and rapidly skimming under the wheels in a way that only happens when you form an affinity with a bike, I began to wonder about the changes that make this bike cost £300 more than its predecessor.

A price of £1215 is likely to horrify a lot of people who've got used to thinking of the products of their home industry as a cheap substitute for the costly brashness of a Honda or Kawasaki four. But in its '75 guise the Trident is in the same league as the Kawasaki, or Laverdas, or (goddamit why not?) the R75 Bee Em. There's always an element of the - grass - is - always -greener syndrome that makes British bikers denigrate British bikes, but even if the home market won't accept that the Trident is in the top league, I'm sure export markets will. The two biggest things that will bring about this acceptance are the electric starter and the superb new styling.

I'm sure one of the reasons for the Trident's lack of popularity in the past was the totally uninspiring appearance, a petrol tank with all the grace and sleekness of a housebrick, drab paint and a motor that sat primly and uncomfortably bolt upright in the frame. That beautiful hunk of motor should be flaunted, not apologised for. The NVT stylists have achieved that very effectively, merely by tilting the engine forwards 15 degrees (like the old Rocket-3), designing a tank that looks deceptively slim from the side, and using an extra bit of polish on the alloy casings.

There's an option of two tank sizes; three or four gallon; and two paint schemes, red with white or white with yellow. Our bike had the large tank that conceals an amazing four gallons, from the side it looks no bulkier than the three gallon option, but a squint from above reveals the extra width that conceals the additional gallon. The classic lines of the tank are set off by tasteful panels of contrasting paint and the good old traditional Triumph nameplate.

Silencers are NVT's annular discharge type, new to the Trident but the same as fitted to the Mk 2A Commando. The upward sweep of the silencers combines with the slope of the engine to give the new Trident an aggressive elan the old version never had. Detail changes in appearance although small, also make a great contribution to the Trident's smooth new look. Seat and sidepanels are redesigned, there's new, tidier switches and neat rubber mountings for the instruments incorporating a warning light console with, for the first time folks, a neutral indicator light.

Of course the changes go more'n skin deep. There's getting on for 50 major design mods, and quite a few more minor ones. Fitting a starter motor involved modifications to the crankcases, clutch and primary chain case. The starter is a car-type pre-engaged, solenoid operated Lucas unit which hides under a satin chromed cover-plate atop of the gearbox. The starter motor pinion meshes directly onto gear teeth on the back of the Trident's single dry plate clutch.

Some of the design changes are not necessarily improvements, merely standardisation forced upon NVT by the American legislators who have decreed that gear change pedals shall be on the left, and brake pedals on the right. Such is the power of the American Dollar, we get not necessarily what we want, but what some politician a few thousand miles across the Atlantic thinks the coddled American public needs., Other things they've foisted on us are standardised and labelled handlebar switches, including an engine kill button, and a neutral indicator light. Switching the gear-change to the left has been achieved without any detriment to the action of the gearbox, in fact NVT have taken the opportunity to make improvements to the camplate and shift lever movement, resulting in slick swapping that's just about as faultless as it can be. I never missed a gear once, and neutral snicks in soft and sure when you're at a standstill.

The crankcases had to be redesigned to accommodate the cross-shaft which achieves the change-over from right to left foot gear shift. It runs from the right hand side, just behind the plate with the 5 speed motif which covers the hole where the gear lever used to emerge, right through to the primary chaincase. Quadrant gears mesh with a gear on the lever shaft on the left extremity, and the other end is linked to the positive stop mechanism.

While making these changes, the development team also tilted the cylinders forward 15 degrees to make more room to accommodate the starter, and to get the weight lower and further forward. This meant redesigning the exhaust, with a cast manifold for the centre pot feeding two small diameter pipes. It looks neater than the old three - into - two system, it's more impressive with four pipes tucked close into the engine, and it also gives more power.

One of the rather exclusive features that boosts the new Trident's status is the hyd-raulically operated rear disc brake — something none of its presently available Japanese competitors can boast. The master cylinder is tucked away behind the brake pedal and the fluid reservoir is out of harm's way underneath the side hinging seat. It works well — too well if anything. The rear wheel can be easily locked on dry roads, if you don't have the dainty tread of a ballet dancer. If that ingenious Mullard anti-lock system being developed by the Transport and Road Research Laboratory had been incorporated it would really have given the Trident the lead in safety. Then with discs front and back the braking system could be coupled as our very own LJKS advocated in his Cog-Swapping column back in August '74.

In addition to the repositioning of the engine, the Trident has a new frame just like the production racer "Slippery Sam" — the most famous Trident of all which notched up three consecutive Production TT wins in '72, '73 and '74, and many other racing honours. The swinging arm is longer, and the front forks are shorter, all to get the weight lower and further forward. The new frame and upswept silencers give the T160V extra Ground Clearance. I never grounded anything, even though the confidence inspired by the Trident's virtuous handling persuaded me to antics that I'm sure upright citizens would deplore.

The electric starter and its associated gubbins, and other additions make up about 401b extra weight over the T150V. It's always been a hefty bike — and now it weighs in at 5221b with a gallon in the.fuel tank, or 5401b with the full four gallons aboard. Still lighter than a few Japanese bikes I can think of, but of course it does mean you have to take low speed turns slowly and deliberately. At anything much above walking pace the weight turns to your advantage by helping that confidence-boosting feel of solid, secure handling. Surprisingly though, side winds affect the bike more than they should do, inducing a slow weave which never turns into a wobble, but is annoying all the same.

I very much doubt this is due to any fundamental handling fault it is quite likely a simple matter of tyre pressures, but with an insanely hectic test schedule, I never got time to experiment with different pressures.

While we're on the moans I've got to tell you that our test Trident laid itself open to all those old British bike jokes about oil leaks. It seeped from the point where the clutch cable enters the primary chain case, and while no great quantity of lubricant escaped it left an unsightly film of gunge over the left side panel. Triumph's chief development engineer Doug Hele was aware of this problem when I mentioned it to him, and he assured me that all bikes leaving the production lines now have a section of tube inserted in the chaincase to seal the oil out of the cable housing.

The Trident's thirst has always been notorious, and our average figure of just over 36 mpg shows things haven't changed. But considering it's one of the fastest 750s around (faster than the Kawasaki H2 which used to have a reputation for speed, and a heavier thirst) that ain't too much to live with. Seems they're working on the problem too with their prototype 850 Trident which Hele reckons could eventually be more economical than the present 750. That's got to be some machine too — ah well, we'll just have to wait.

But until that 850 version becomes a commercial reality, I've got a feeling the T160 is going to do a lot for the British industry's flagging reputation, here and abroad. Let's just hope it's going to be the answer to NVT's financial problems too.

Bill Haylock

Summary

LOOKING back on this, only the second all-British Giant Test in Bike's history, we can't help remembering that despite the usual frustrations of unbelievably tight time schedules, crummy weather, and a thousand and one other things clamouring for priority, those two machines really were good to ride. We used any and every excuse to take them down the road, sometimes pushing them to the limit, exploring every last ounce of potential; sometimes cruising free an' easy, relaxing in the feeling of unruffled confidence they convey. That's the first impression you get from riding the Norton and the Triumph, and the one that always seems to come to mind afterwards — they're so manageable. It's so damn easy to jump aboard and go places without having to worry about a peculiar handling or a particular power characteristic: you just get on and go.

Since its initial success back in '67 the Commando has lost a lot of ground in the battle of the giants, but the latest specs plus the extensive revision of known weak points slam it right back into the heat of the competition. With a rather dramatic price rise — over £200 up on the previous model — it's certainly no longer a cheap alternative machine, although it still undercuts the all powerful Kawasaki Zl and Norton Triumph are confident they can hold the price.

The final outcome of the Commando story remains to be seen. So many factors way beyond the limited scope of motorcycling will influence its future, yet while national economies tremble, bikers at least will have difficulty finding a more satisfying way of losing their troubles.

Meanwhile, the Trident now has sophistication, frills and finery the British purists will probably abhor — but it is still a fit machine to carry into the seventies (and eighties maybe) the tradition that produced such British classics as Brough Superior, Manx Norton and, of course, the Triumph Speed Twin.

It costs fifty quid above the Commando's list price, and £250 more than the T150, but it also offers more refinement and a hell of a lot more style than either the old Trident or the new Commando. And it has as much to offer as many machines in the swelling ranks of luxury bikes costing as much as a couple of grand.

Of the two bikes the Trident must have the brighter future. The Norton twin inevitably looks dated, however well it performs, but the triple powerhouse is, with the benefit of its new styling, one of the most exciting looking engines around. And the way it performs compared to most of its opposition shows the design still has plenty of youthful virility. What's more the Trident still costs roughly the same as a British Leyland Mini (yeeuch — excuse me while I vomit). I know which I'd sooner spend 1200 notes on. •

Source Bike 1975

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |