|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

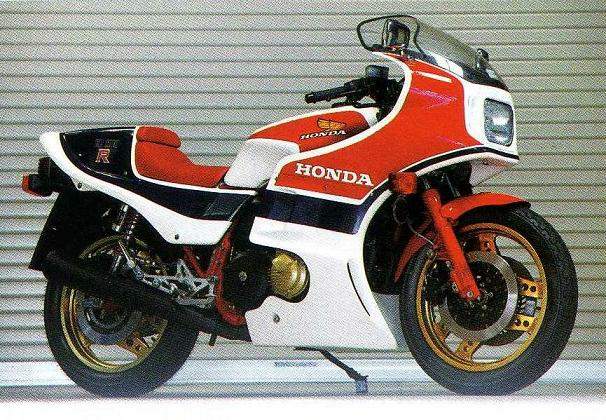

Honda CB 1100R BC |

| . |

|

Make Model |

Honda CB 1100R BC |

|

Year |

1982 |

| Production | 1500 units |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, transverse four cylinders, DOHC, 4 valve per cylinder |

|

Capacity |

1062 |

| Bore x Stroke | 70 x 69 mm |

| Cooling System | Air cooled |

| Compression Ratio | 10.0:1 |

|

Induction |

4x 33mm Keihin carbs |

|

Ignition |

Electronic |

| Starting | Electric |

|

Max Power |

120 hp / 87.5 kW @ 9000 rpm |

|

Max Power Rear Wheel |

106 hp @ 9000 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

98 Nm / 72.5 ft-lb @ 7500 rpm |

|

Transmission |

5 Speed |

| Final Drive | Chain |

| Frame | Steel tube double cradle |

| Front Suspension | Adjustable telescopic hydraulic fork |

| Rear Suspension | Swinging arm fork with adjustable Telehydraulic shocks absorbers |

| Front Brakes | 2x 296mm discs 2 piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | Single 296mm disc 2 piston caliper |

|

Front Tyre |

100/90-18 |

|

Rear Tyre |

130/90-18 |

| Dimensions |

Width 805 mm / 31.7 in |

| Wheelbase | 1490 mm / 59 in |

| Seat Height | 795 mm / 31.3 in |

|

Dry Weight |

235 kg / 513.7 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

26 Litres / 6.9 gal |

|

Standing ¼ Mile |

11.3 sec / 190 km/h |

|

Top Speed |

230 km/h / 143 mph |

|

Road Test |

| . |

The model designations are CB1100RB (1981), CB1100RC (1982), and CB1100RD (1983). The 1981 'RB' was half faired with a solo seat only. The 82 and 83 models have different bodywork including a full fairing, aluminium fuel tank, and pillion seat covered with a removable seat cowl. The 82 (RC) and 83 (RD) were largely similar in appearance, yet with considerable differences what concerns the full fairing and dashboard layout. None of the faring parts of any of the 3 models are interchangeable with one another. Other differences include the paint scheme, rear swing arm design and color and front fork design.

1981 type BB is a unique model with a half fairing, similar to the CB900F and a single seat. Comstar wheels, front 19 inch, rear 18 inch.

1982 type BC has plain red and white/blue colour scheme, yellow wing in the logo on the tank and red swingarm. Exhaust is matt black, boomerang wheels, both 18 inch.

1983 type BD has metallic red and white/blue colour scheme, silver logo and a silver square swingarm. Exhaust is black chrome, boomerang wheels as per 1982.

Motorcycle USA review

To anyone who likes racebikes, the CB1100R sends out mixed

messages. The first thing which strikes the interested observer is the bike's

size. Parked up in the paddock, the Honda is not your lithe, toned sprinter

waiting to trot out and compete in the 200m - more a Football defense warming up

ready for a head-crunching pitched battle.

Yet look at the same defense without his helmet and you will see both plenty of

scar tissue - and a shirt stretched tight by bulging muscle. The odd lump of ear

might be missing but this is no couch potato wobbling out on to the field. Note

the magnesium clutch and alternator covers and listen to the tenor wail of the

1062cc engine, and it becomes readily apparent that, beneath the corrosion,

scrapes and immense size there lurks a real racing motorcycle.

The CB1100R is one of a number of bikes Honda have produced

over the years to circumvent homologation rules for racing. Series organisers

will demand that a certain number of examples of a particular machine must be

produced in order to qualify with their regulations. For example, World

Superbike is run with machines based, very loosely, on production motorcycles

which the ordinary customer can - in theory at least - walk into a showroom and

purchase. Manufacturers ruthlessly exploit and bend the regulations right up to

breaking point and so there have been some extremely interesting motorcycles

sold over the years as "homologation specials." The CB1100R is one of the best

since it took the rulebook right to the edge of legality and then, initially at

least, fell over the regulatory cliff.

Take yourself back to 1980 when Grand Prix racing was still ruled by 500cc

two-strokes. These were pure racebikes and were a million miles away from

anything in mass production. Both Yamaha and Suzuki had attempts at bringing the

GP world to the road rider with four-cylinder two-strokes, but the truth was

that the ordinary motorcyclist on the street wanted a big, four-cylinder

four-stroke.

The next bit of history is that one of the most prestigious one-off races in the

world during the 1970s and '80s was the Castrol Six-Hour race held at Amaroo in

Australia. In terms of an advertising event to promote Asian sales, this event

ran a close second to the Suzuka Eight-Hour race and which spawned some equally

exotic machinery.

Honda was determined to win this race and so took their existing CB900F and gave

it a full race make-over. The CB1100R was to be no tweaked up road machine but,

as far rules could be stretched, a full-blown racebike. The first job was to

lighten and stiffen the CB900F frame. This was done by increasing the quality of

the tubing and by making the frame in one piece instead of having the right-hand

down-tube removable to help with servicing. Even so, with a wheelbase of 1475mm

(58"), and a saddle height of 805mm (31"), this is no Moto Martin or Harris race

frame.

The engine received even more treatment. The CB900 lump was bored to 70mm,

resulting in a whopping capacity of 1062cc. A race camshaft was put into the

engine along with forged pistons, which increased the compression ratio to an

eye-watering (for the day) 10:1. This high compression ratio has proved to be a

consistent wrecker of the starter motor clutch rings over the years on bikes

used on the road. A close-ratio transmission went into the gearbox and the drive

was protected with a wider primary chain and lighter clutch.

What could be seen was, in some ways, even more sensational than what was

hidden. The road bike's high bars were retained but a huge bikini fairing

wrapped itself round the cockpit area. Behind the fairing was an equally mammoth

six-gallon alloy fuel tank, and the world's most comfortable race seat ensured

the pilot was going nowhere as he wrestled the big Honda round the racetracks.

Ultra lightweight magnesium, painted with traditional gold paint to reduce

corrosion, was used for the clutch and alternator covers.

| . |

The chassis was still very much late '70s with a traditional twin-shock rear end

and steel swinging arm, although the fork did have air assistance in lieu of

anti-dive. The reality of the situation was a racebike which weighed in at an

incredible 563 lbs - over twice as heavy as its Grand Prix cousins. At the other

end of the scale, the 1062cc engine produced a walloping 115 bhp at 9,000rpm -

not that far behind its contemporary GP thoroughbreds.

In summary, the CB1100R was a true classic dinosaur - big, brutal and, by the

standards of the day, monstrously powerful.

Racing the CB1100R

The fact that I was able to ride the bike at all is thanks to the efforts of

Peter Spowage and Clive Brooker - the driving force behind the Historic

Endurance Racing Team. Because of the enthusiasm of Clive and Peter, some of the

wonderful, old long-distance racebikes from the 1960s, '70s and early '80s can

still be seen in action at events all over Europe. The CB1100R I was about to

ride was the genuine ex-Ron Haslam bike on which Ron won the MCN Street Bike

series in 1981 and 1982. At the time, this was the most important streetbike

series in the world. At present, the CB1100R is owned by a secretive enthusiast

who allows the Historic Endurance Racing Team to demonstrate the bike - provided

his anonymity is protected.

One of the events on the team's tour is the "Bikers' Classic" festival held at

Spa Francorchamps in Belgium. Although heavily spiced up with bells and

whistles, thanks to ex-world champions and mouth-watering GP bikes, the event is

essentially a giant three-day track bash for classic race bikes. Legally, it is

not racing - but it would take an expert eye to split the difference.

As I lined up with a host of late classic racebikes it soon became clear that

the CBR was going to be the centre of attention. With ex-works rider Ron

Haslam's name emblazoned on the fairing, I faced a stream of autograph hunters

and, except for being taller, fatter, having a lot less hair and about 1% of

"Rocket Ron's" riding ability, I might well have got away with the deception:

With the odds stacked against me I didn't even try.

Out on the track, it becomes clear that the CB is carrying its age well -

despite being unrestored. The 115 horses allowed us to run with the faster

Triumph Triples, and once the glazing had been scrubbed off the pads, the

Honda's discs were well up to hauling down the 600-plus pounds of heavy metal

which constituted the Honda fully fuelled.

Down the straights on braking, the CB1100R runs with the hot classics without

too much trouble. The problems begin on the corners. This needs explaining. A

decent BSA/Triumph triple pushes out well over 90 bhp and weighs around 340 lbs.

That means that the Honda is carrying almost the weight of a pillion passenger

and a full set of touring luggage extra compared to a pure classic race machine.

Running modern race Avons, the Triples go round corners like 125 GP bikes and

also get their power on extremely early. By contrast, the Honda carries Metzeler

road tyres and it is Peter's policy to run these at very low pressures.

Apparently, Honda Britain ran 39 psi in the front tyres in contrast to the 27

psi which Peter puts in the Metzelers. The result is that although the Honda is

wonderfully planted on long corners, it is reluctant to change direction. This

where the classic racebikes do their disappearing act.

Still, none of this matters much compared with the delight of riding such a

thoroughbred machine. The gearshift is in the perfect position, being on the

right with up for down. Until anyone has ridden a machine with this

configuration, it will never be apparent what a con trick the Japanese worked on

us with a left-hand change running the wrong way. The change is sweet, light and

bulletproof and the motor not at all cammy. Simply wind on the big Four and it

goes faster and faster - with 135 mph popping up on the speedo a couple of times

a lap.

At 5' 11", I am too tall for a road racer, so I love the vast amount of space in

the cockpit and behind the fairing. The handling is impeccable, the brakes

excellent. This is a bike I really could fancy taking home with me. It is both

charismatic and, taken in context, flawless. Carrying a set of sticky Avons or

Bridgestones, many modern Superbikes would be given a seriously good run for

their money by the 20-year-old Honda.

As I return the bike - thankfully still in one piece, since it is priceless - I

am left in awe at the size and quality of the marriage tackle inside the

leathers of Haslam, Dunlop and Gardner. It is one thing being tucked in behind

the fairing pretending to be racing, but these stars of the muscle bike era must

have been seriously well equipped in the testicular department to race a bike as

big, heavy and powerful as the CB1100R in anger. My heartfelt admiration and

salutations to you all.

Source Motorcycle USA

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |