|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

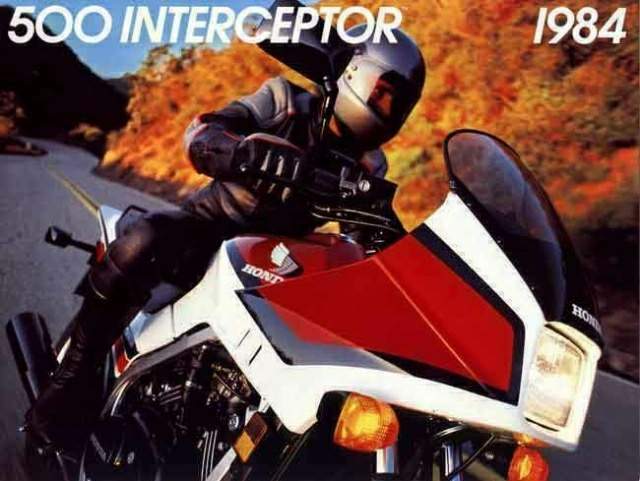

Honda VF 500F Interceptor

|

| . |

|

Make Model |

Honda VF 500F Interceptor |

|

Year |

1984 |

|

Engine |

Four stroke, 90°V-four cylinder, DOHC, 4 valve per cylinder |

|

Capacity |

498 cc / 30.3 cu-in |

| Bore x Stroke | 60.4 x 44 mm |

| Compression Ratio |

11.0:1 |

| Cooling System | Liquid cooled |

|

Induction |

4x 32 mm CV |

|

Ignition |

Transistorized |

| Starting | Electric |

|

Max Power |

70 hp / 51 kW @ 11500 rpm |

|

Max Torque |

43 Nm / 4.2 kgf-m @ 10500 rpm |

| Clutch | Multiple plate coil springs |

|

Transmission |

6 Speed |

| Final Drive | Chain |

| Frame | Double cradle |

|

Front Suspension |

Air assisted 37mm forks |

| Front Wheel Travel | 140 mm / 5.5 in |

|

Rear Suspension |

Pro-link air assisted 4-way adjustable rebound damping |

| Rear Wheel Travel | 115 mm / 4.5 in |

|

Front Brakes |

2x 255mm discs 2 piston calipers |

|

Rear Brakes |

Single 255mm disc 1 piston caliper |

|

Front Tyre |

100/90-16 |

|

Rear Tyre |

110/90-18 |

| Dimensions |

Length 2070 mm / 81.5 in Width 760 mm / 29.9 in Height 1175 mm / 46.3 in |

| Wheelbase | 1420 mm / 55.9 in |

| Seat Height | 800 mm / 31.5 in |

|

Dry Weight |

185 kg / 407 lbs |

| Wet Weight | 20 kg / 454 lbs |

|

Fuel Capacity |

17 Liters / 4.5 US gal |

|

Standing ¼ Mile |

12.6 sec / 102 mph |

|

Top Speed |

206 km/h / 128 mph |

|

Road Test |

Cycle Magazine 1984 |

| . |

Yet within that framework there's room for individuality, for character. Motorcycles, like people, have personalities. There are cruiser-style bikes, for instance, awash in glitter and that swagger down the boulevard like some kind of two-wheeled Mr. T. There are big-bore sport bikes, motorcycling's answer to football running back Herschel Walker, machines that have all the muscle in the world but can still pivot around corners with the grace of a gazelle. And let's not forget about touring bikes, each of which is a mammoth, Orson Welles of a motorcycle that stares you in the eye and announces that "We will take no trip before its time."

Honda's newest middleweight sport bike—actually, the first middleweight sporting machine from that company since the beloved CB400F of the mid-Seventies—the VF500F, also has a distinct personality: It's the Mikhail Baryshnikov of the motorcycle world. Baryshnikov, for those of you who aren't familiar with the name, is an internationally renowned and immensely talented ballet dancer. He moves with extraordinary grace, and despite his relatively small size is, pound for pound, one of the strongest athletes in the world.

That description could just as easily apply to the VF500F, the US. market's smallest Interceptor. Derived from a 400cc V-Four-powered model that Honda produces for Europe and Japan, the 500 comes in a small package; but its 498cc engine hammers out a claimed 68 horsepower, enough to propel the 432-pound bike (gas tank half-full) into performance parity with its 550cc and 600cc air-cooled inline Four competitors.

The VF500's engine is something of a mongrel in that it combines parts and technology borrowed from the VF400F and the VT250, a 250cc V-Twin mini-Interceptor also sold in Europe and Japan. The easiest way to envision the 500's engine is as a strengthened VF400 bottom end with a pair of VT250 top ends grafted on side-by-side. And, in fact, the 500 Four puts out exactly twice the horsepower that Honda claims for the VT250 Twin.

Other engine details are typical Honda V-Four fare. The highly oversquare motor is liquid-cooled, with a 17-row radiator mounted in front of the frame's front downtubes and snuggled up to the forward pair of cylinders. The cylinder banks are angled 90° to one another and have three undersized fins on each side, partly for additional cooling but mostly as a styling exercise. A quartet of carburetors, 32mm Keihin CVs, is nestled between the cylinders and takes in air through a pleated-paper element in an airbox just below the gas tank. The airbox's location means the tank has to be removed for filter servicing. Inconvenient but necessary, given the space limitations and the need for a fairly straight intake tract.

As with the other engines in Honda's V-Four group, each cylinder in the VF500 has four valves, opened by finger-type followers driven by double overhead camshafts. Valve lash is set via threaded adjusters. Looped around each cam is a double-row roller chain, which makes three different types of chains that Honda has used to drive the camshafts in its V-Four engines. The 750 Interceptor uses inverted-tooth Hy-Vo type chains, while the 1000 Interceptor gets by with single-row roller chains. Honda claims, however, that the 500's double-row roller chains are the most efficient. And while the power-transmitting differences between the three types of chains are minimal, at the revs the 500's engine is capable of attaining—redline is set at a stratospheric 12,000 rpm, a full 1500 rpm higher than the class' previous rev-king, the Yamaha FJ600—even the tiniest of differences can be important.

A hydraulically activated clutch is used on the 500; and because it, too, was derived from the VF400's clutch and only uses four springs to press things together, the 500 gets nine friction drive plates and eight steel driven plates to handle the increased power its pumped-up engine puts out. The clutch connects the engine to a six-speed gearbox in which gear selection is accomplished by a planetary gearchange mechanism, unique to the VT250, and the VF400/ 500. This design gives a crisp feel to the shifting procedure and encourages a light touch on the shift lever. Sometimes too light. Several times during our 3000-mile-plus test session, the rider engaged a higher gear only to have the gearbox shift back down a gear by itself. A lightly firmer tug on the lever always assured that the gearbox stayed in the chosen gear.

Just as ballet-goers are more interested in Baryshnikov's arabesques, pirouettes and tour en I'airs than his bio-rhythm chart or electrocardiogram plots, would-be 500 Interceptor buyers will likely care more about how the bike's engine works than about the technical details of why it works. And if anyone is concerned that a 12,000-rpm redline means lots of clutch-slipping to get underway and an engine that falls flat on its face below 8000 rpm, his fears are unwarranted. The VF500's engine will never be classified as a torque monster, but it pulls with surprising oomph from just about any rpm, and it rushes to its redline with nary a peak or valley in the power curve. Yes, for really impressive acceleration, the tach needle needs to be kept in the upper one-quarter of the rev-range, but dropping into the middle rpm regions won't cause the bike to blubber like some sort of 125cc motocrosser with turn signals.

Wide powerband or no, most riders will keep the 500's engine wound up anyway, for it revs so freely that it entices such behavior. As one of our staffers so aptly put it, "This thing lives to bury the tach needle."

Bury that needle for a half-mile or so, and the VF will be running in excess of 122 miles an hour, which is faster than either the FJ600 or GPz550, and just a tad slower than Suzuki's GS550. At the dragstrip, the Honda clocked a 12.66-second run at 102 mph, which is identical to the GPz's performance and slightly below that turned in by the FJ and GS. Bear in mind, however, that these quarter-mile numbers were clocked over a period of nine months at different tracks using different riders. In other words, they are not directly comparable. But they do show that the VF500F, regardless of its displacement handicap, is in the hunt, acceleration-wise.

Despite all the high-revving fun our test 500 was put through, it still managed to return more than 50 miles to the gallon of gasoline. The bike generally went about 150 miles before the quick-fill-lookalike petcock needed to be switched to reserve, which was good for about another 50 miles.

There are a few criticisms we can direct toward the engine, but they are comparatively minor ones. The engine is mounted solidly in the frame, for example, so it transmits a small amount of vibration to the footpegs and handlebars. At cruising speeds the rider really has to search for the vibes to feel them, but as the revs increase so does the level of vibration. Still, it's more of a throbbing than it is a high-frequency buzzing, and it's nowhere near as annoying as the vibration felt on most other mid-displacement bikes.

Cold-starting also presents some problems for the Interceptor. The engine leaps to life easily enough in the morning, but with the choke full-on the engine turns at a way-too-high 4000 rpm. Backed off to a still-high 3000 rpm, the engine will slowly lose revs until it stalls. Consequently, a VF500 rider soon learns to let the engine rev for the first few miles of travel and then move the choke to the full-off position, simply because the bike is reluctant to run anywhere in between.

Some riders also complained of a small amount of snatch in the 500's driveline, enough that indelicate operation of the throttle in first and second gear would result in some jerkiness. Smoother riders or those with experience on snatch-prone shaft-drive motorcycles didn't feel there was any excess freeplay in the driveline.

Despite those complaints, the VF's engine is easily its most exotic component. But that says more about recent strides in frame and suspension technology than it does about any shortcomings in the Honda's chassis, which is about as up-to-date as possible.

In the front, a 16-inch wheel and a wide Bridgestone Mag Mopus tire are kept in contact with the road by a fork assembly that incorporates Honda's TRAC anti-dive system. An aluminum brace ties the black-painted fork sliders together—important because the TRAC mechanism works only on the left fork leg—and serves as the only mounting point for the plastic front fender. Each 37mm stanchion tube has an air fitting, and Honda recommends 6 psi as the maximum static pressure. Unlike the bigger Interceptors, the 500 has no damping adjustment on the fork, a concession to price in the cost-conscious middleweight class.

That Showa-built fork heads up a frame constructed of silver-painted, rectangular-section steel. Well, at least the majority of the frame is rectangular in section; the parts of the frame that are covered by the seat and side panels use standard-issue round tubing. The swingarm, however, doesn't need to be painted silver to resemble aluminum, for it's already made of that material, in cast form. The arm attaches via needle-bearing-equipped links to a single shock buried in the middle of the bike. The Kayaba shock is air-adjustable (Honda recommends 7-21 psi), its air fitting reached by taking off the left sidepanel. To get at the rebound-damping adjuster, which is a small, four-position knob atop the shock body, the seat must be unlocked and removed.

All of this type of hardware is quite common in today's exotic sportbike market, but there's nothing at all commonplace about the VF500F's handling. For just as the 500's engine lives to bury the tach needle, so does the chassis live to bend its way around corners. The bike really shines on twisty backroads—in fact, the twistier the better. On a dream backroad, one that spins and slues and ties itself into knots, one with a minimum of literbike-favoring straightaways, this Interceptor could very well be the quickest way to snake from Point A to Point B.

With near-maximum levels of air pumped into the fork tubes and rear shock, and the TRAC anti-dive and rear rebound damping both adjusted to their highest settings, the Honda is about as neutral a handler as there is these days. No matter how crazily the horizon gets tilted, the VF always seems unruffled, as though it still has plenty in reserve. As a result, the bike is a confidence-builder par excellence.

The rider doesn't feel any less confident when those corners get extremely fast, either. Despite a fairly steep rake of 27 degrees and a relatively short, 56-inch wheelbase, the VF simply refuses to get unsettled when taken through top-gear sweepers. Likewise, S-turns don't bother the Interceptor, meaning that flicking the bike from hard-right to hard-left and back again is anything but a white-knuckle experience. In fact, the Honda handles these maneuvers with such ease that it almost dares the rider to go back and take that last corner at a faster speed or bank over a few degrees further or delay braking for another heartbeat or two.

Not only is the 500's chassis up to that level of enthusiasm, but so are its brakes. Three 10-inch discs are squeezed by new-style twin-piston calipers that are a little lighter than last year's versions and very much have a Fast-Freddie-uses-ones-just-like-this look to them. The front brake lever takes a fairly firm pull—not much happens during the first part of its movement—but from that point on, the feel is good and the stopping distances are short. During hard stops, the rider is aware of the TRAC mechanism's presence, but only when it's set to the No. 4 position. The front end still compresses fully, but at a slightly reduced rate.

One of the elements that makes the Interceptor such a backroad weapon detracts slightly from its abilities as a straight-line tourer. The bike's seating position, which is ideal for charging apexes and hanging off in fast corners, is a little cramped, especially for riders who crowd the six-foot mark. The culprit here is the relationship between the seat and the footpegs. The pegs are placed high and to the rear so they stay off the deck during full-tilt maneuvers, but that location also forces an awkWard bend in the knees. The seat does its part, as well, to keep Gold Wing lovers from becoming Interceptor-mounted tourers. Thin on padding because of its scooped-out shape, the seat allows only one position, which soon becomes tiring. Run one tank of gas through the 500 without encountering a series of curves to break the monotony, and it's time for a leg-stretching, butt-denumbing rest period.

Any other complaints about the Interceptor fall into the category of nit-picking. A couple of staffers thought the calibrations on the 150-mph speedometer were too crowded for easy reading. The rear-view mirrors also came under fire for being too convex. They give an extremely wide-angle view, which is good for peeking at what's coming up on either side, but they also make it hard to judge distances. And like the majority of narrow-gauge sportbike mirrors, the 500's don't provide a clue as to what is approaching from directly behind without the rider tucking in his elbows.

It's hard to criticize the 500 Interceptor's styling, though. Honda hit on a winning formula with last year's 750 Interceptor and has carried it through first to the 1000 and now the 500. And if anything, the 500 is the crisper-looking of the three. All the Interceptors may have been cut from the same block of stone, but the 500's sculptor used a finer chisel. During our travels on the VF500, the bike's appearance always drew the same reaction from people. From motorcycle nuts to gas station attendants to little old ladies, almost all finished their unsolicited critiques of this particular Honda with, "Nice bike."

Indeed it is. But that doesn't begin to tell the story of this motorcycle. A bike that looks this good, handles this well, has such a wonderful engine and costs no more than its competitors is more than just a "nice bike." It's damn near irresistible.

And not irresistible to just the blood-ied-knee canyon-crazies. Cycle World's staff is as diversified a group of motorcycle enthusiasts as you're likely to find, and to a man they picked the Interceptor as the middleweight bike to have when it comes time to blast down a winding country two-lane. The GPz550 might be a better choice for all-around transportation because of its more-spread-out seating position and rubber engine mounts. But for straightening out the kinks in a twisty piece of road, the 500 Interceptor is the best bike in its class. Or, for that matter, maybe even in any class. SI

Source Cycle World 1984

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |